Artist Statement:

“During the 1960s, I think, people forgot what emotions were supposed to be. And I don’t think they’ve ever remembered.”

~ Andy Warhol

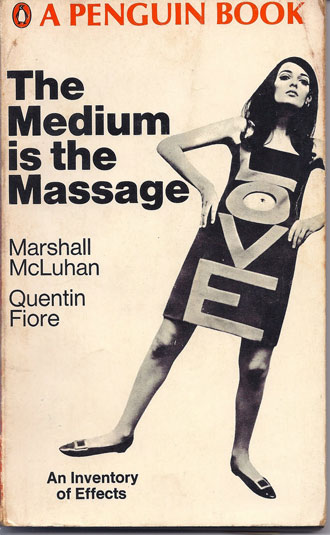

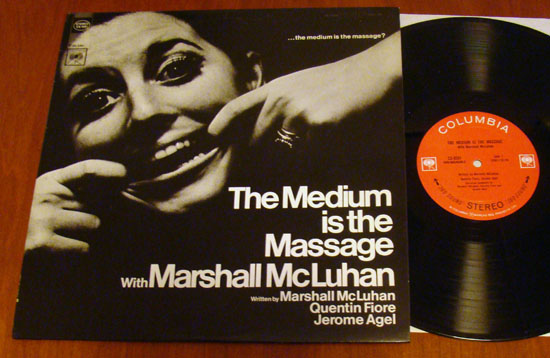

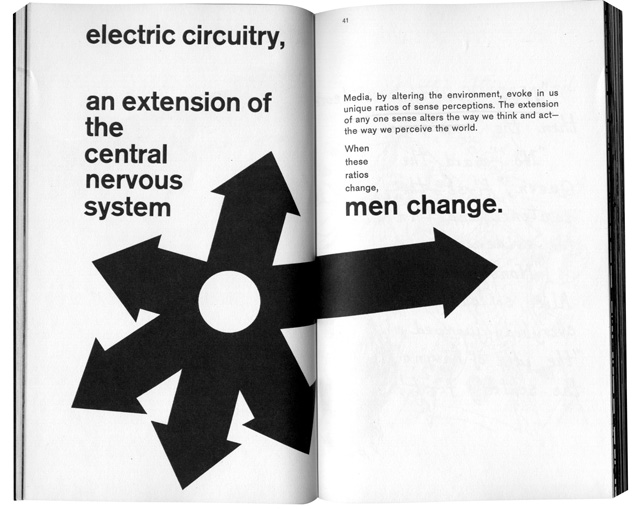

Mcluhan wrote his stunningly prescient monumental work, one of twelve books and hundreds of articles, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, in 1964. He followed up with “The Medium is The Massage: An Inventory of Effects” in 1967. The record you hear arrived after that, but it embodied the same ideas. The baseline subject that would preoccupy almost all of McLuhan’s career was the task of understanding the effects of technology as it contextualized popular culture, and how this in turn affected human beings and their relations with one another in communities. For him, everything was connected. Because he was one of the first to sound the idea that electronic media and pop culture were eerily interconnected, McLuhan gained the status of a cult hero and “high priest of pop-culture”.

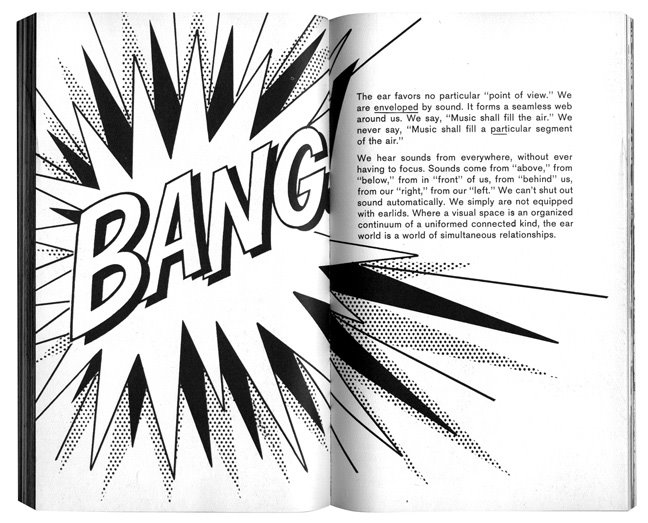

Acoustic space, pattern recognition: boundless, infinite play of text and thought – that’s what you need to think about when you listen to this album. The record version of the “Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects” project was meant to embody some of the issues that the graphic design and radical use of new fonts and images to enhance the text of the book and create a dynamic linkage between how the collision of fonts and graphics would work and how they could be represented in sound. The whole thing is presented as an audio collage focused around McLuhan’s own voice reading parts of the book. There are other “character” voices—’the old man’, ‘the Hippie chick’, ‘the Irishman’, ‘Mom’, ‘the little girl’, etc.—who utter McLuhanisms, snatches from Pop culture, and excerpts from Finnegans Wake and The Iliad. Weaving amongst these is a very 1960s selection of jazz, classical, and psychedelic pop musics. This is all topped off with incursions from the recording engineer, backwards tape effects, sped-up and slowed-down voices, ambient recordings, and a whole jungle of other Foley and sound FX. One could argue that the book was as much about the graphics as it was about creating a place where the images could embody the philosophy graphic design that Mcluhan advocated –the record was the audio version of the same process. As Mcluhan once said: “For tribal man space was the uncontrollable mystery. For technological man it is time that occupies the same role.”

The record version of the “Medium is the Massage” presents that as a DJ mix – it presents the entire book as a series of samples, just like a mix-tape.

Think of this record as a collection of some of Mcluhan’s spoken texts recorded, collaged, cut-up, spliced, diced, ripped, mixed, and burned. It’s a mix tape made in a different era – before the rise of digital media files, but it has the same kind of resonance of a mix of any current sound art project one could care to name.

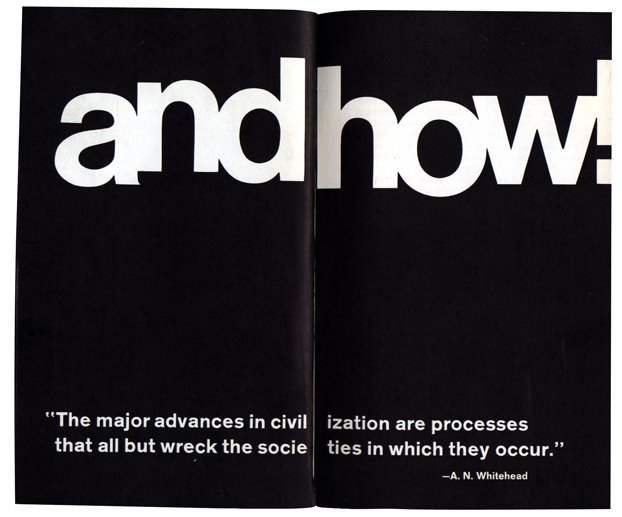

His thought is frequently reduced to one-liners: he was a philosopher the sound bite, which sum up the more complicated content of his probing and rigorous examination of “the media,” a word that he made more popular than almost any other thinker. Concerning the new status of humanity in a technological, and media-dominated society, he wrote:

If the work of the city is the remaking or translating of man into a more suitable form than his nomadic ancestors achieved, then might not our current translation of our entire lives into the spiritual form of information seem to make of the entire globe, and of the human family, a single consciousness?

How would you translate that into an album?

It goes without saying that hands down, Mcluhan was a master of the freestyle. Think of him in terms of hip hop, wordplay, and above all, how you can create new forms of viewing culture from the intertextual flow of words put at the service of technology. This is no pun. It is a fact. With phrases like

Affluence creates poverty.

or

All media exist to invest our lives with artificial perceptions and arbitrary values.

or even better

Darkness is to space what silence is to sound, i.e. the interval

McLuhan both announces the existence of the “global village” another word he is credited for coining, and predicts the intensification of the world community to its present expression, all with a musical sensibility of quotation and citation. That is what we call a “riff.” All of this was done in the early 1960s at a time when television was still in its infancy, and the personal computer was almost twenty years into the future. He was the embodiment of what writers of his era like Samuel Delaney or Philip K. Dick turned into prose, but somehow he always gave us the best way to navigate the uneasy tension between context and content.

========

You know Mcluhan was onto something deep, like the flow of prose from James Joyce to people like Jonathan Lethem, William Gibson, or a tribal griot in Africa. Mcluhan’s understanding of the scope of changes being wrought on the collective consciousness of the 1960’s is hard to overestimate. What always surprises me is the fact that there was no record of his records. When you hear this group of recordings, you realize that in addition to creating stunning works of theory, Mcluhan had an incredible grasp of how sound would condition any situation. He made “mix tapes” in the same way that his fellow Canadian, Glenn Gould, would create tape collages of his piano playing. That’s just a way to say that he was a master of how a recording could transform an idea. When you record something, basically you look at a fragment of a mirror held up to a captured distilled theater essence of what it means to be a human being. Our modes of creativity in the 21st century are still catching up with his prophecies. Social media networks and the whole issue of how we are rapidly turning ourselves inside out are like reflections in “real time” of the issues that Mcluhan grappled with on this record version of The Medium is the Massage. When you look at what composers like King Tubby, Steve Reich, or The Firesign Theater were doing with collage and tape loops in the 1960’s you can easily see the connection between this record and the basic fact that people began in to use the studio as an instrument in its own right. Let’s not forget that at the same time that Mcluhan made this record, the Rolling Stones were using fragments of tape on records like “Their Satanic Majesties Request” and the Beatles had released material like “Revolution Number 9” – so one can hear the almost psychedelic edge of the insistence on having simultaneous fragments of records playing at the same time.

I guess Mcluhan really understood very early on what Baudrillard liked to call “the ecstasy of communication” and applied directly to his equivalent of what we would now call a “mix tape” (even though we’re totally digital these days). From films like “Inception” to “The Matrix” on over to theoreticians like Edward Bernays (who coined the term “public relations” and the “engineering of consent”) on over to what it would be like to be a technician monitoring a mobile cybernetic weapons platform like a Predator Drone, it’s hard not to see the impact of Mcluhan’s thinking on modern life. We live in his shadow. I’m thinking of him as the equivalent of modern Socrates or Plato, mixed with the near awe inspiring ability of his to condense everything into high brow puns with a wit that is unmatched in any writer I’ve ever encountered. He’s so good with language that I view him as the equivalent of a hip hop seer, a person who understands the semiotics of the everyday gathered into a bundle of unpredictable and stunning prose. It’s with that in mind that I invite you to listen to this incredible audio essay. This album is a unique statement of the 1960’s era when alot of the issues that I’ve mentioned where coming into the foreground of how people thought culture could operate, and one can see with our 21st century era of the mashup, the remix, and the erased sense of origin and “postmodernity” how eerily prescient Mcluhan was. It’s almost as if he were so far ahead of his time that this album was made last year, not almost half a century ago. It’s that deep.

Enjoy and listen with all ears and eyes wide open. As Mcluhan once wrote: As the unity of the modern world becomes increasingly a technological rather than a social affair, the techniques of the arts provide the most valuable means of insight into the real direction of our own collective purposes.

Think of this album/mix tape as a work of art of the highest order – it’s a child that any parent could be proud of. Again, to use one of Mcluhan’s puns “diaper spelled backward is repaid. Think about it.”

With this album, McLuhan is announcing what Don Delillo says is a world of people who worship the objects of their own invention in the form of cell phones and high speed cloud computing, and like JG Ballard, accept the blessings of Coca-Cola and dresses by Donna Karan as the mark of divinity – for Mcluhan, this isn’t “un-normal” it’s just another form of literary anthropology. The fact that more people watch media online, or on television than go to church is nothing new to us, but it evoked a series of cascading crises for anyone who tried to think of the “norms” of modern humanity – it would be considered one of the tell-tale signs of a cultural shift in history for McLuhan; a shift which has been imperceptible to most, and devastating to all who accept the idea of the “American Dream” that Mcluhan writes about so eloquently. If anyone doubts McLuhan’s warning that “we become what we behold,” they could reflect on the all consuming desire of average kids to be like Michael Jackson, Steve Jobs, Madonna, or Lady Gaga or Danger Mouse: a desire that has resulted in a culture of plastic surgery and drive-by shootings to obtain tennis shoes, a culture that leads us to ask questions of the global commerce that drives culture. Is this a good or bad thing that people all over the world are listening to the same songs, downloading the same mixes, and checking out the same multi-media whether they’re in the North Pole, Sudan, Somalia, Colombia, Japan, or Timbuktu? McLuhan believed that humanity has always been fascinated and obsessed with these issues, but too frequently we choose to ignore or minimize the actual fact that history never stands still. We live the present, but are haunted by the past. Try to make a mix out of that, and you’ll understand why this album is such a rare treat. It’s an instant classic. I hope you enjoy it.

in peace

Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid

New York, 2010